In last month’s blog post we explored the notion of community leadership in tough times, the unique challenges sometimes placed on community leaders and the role emotional health can play in helping such leaders navigate these challenges.

This month I’d like to continue this line of thought in the context of Australia’s upcoming referendum on the establishment of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

William Barak was a community leader. Born in 1823, he eventually became an elder of his Wurundjeri people, traditional owners of the lands that make up much of today’s greater Melbourne (Naarm) area.

Looking back, I don’t think any of us can comprehend the sheer scale of the challenges William Barak must have faced as a leader in his community. His people’s way of life had been turned upside down by the arrival of a very different and quite alien culture. In a very short time, they lost access to most of their traditional lands. Their culture was clearly under threat, with ceremonies disrupted, the prohibition of story and language, and the arrival of ‘religion’, to name some of the impacts and controls they experienced.

Yet history records that Barak displayed many of the aspects of emotionally healthy leadership I discussed in my last post. He remained resilient, his responses were thoughtful and he worked to build and maintain respectful relationships with the new arrivals. Barak became a prominent negotiator, forming bonds with governors, politicians and other key colonial figures of the time.

In 1886, Barak presented a petition to the Victorian government opposing the Aboriginal Protection Act, which effectively gave the government wide-ranging controls over the lives of Indigenous people. Barak argued that his people should have the same freedoms as the white population. Unfortunately, Barak’s petition was ignored.

This was not the first time, and it certainly wasn’t the last time, that appeals from Aboriginal Australian have been disregarded. For over 200 years, numerous petitions have been made to governments by Australia’s First People, while the widespread colonial practice of keeping indigenous people ‘in their place’ has been maintained and reinforced in Australia over and over again.

Yet, through it all, numerous First Australian leaders have continued to display emotionally healthy leadership, patiently working with successive governments to try and improve the conditions of their people and emphasising their rights as the original custodians of the lands that make up modern Australia.

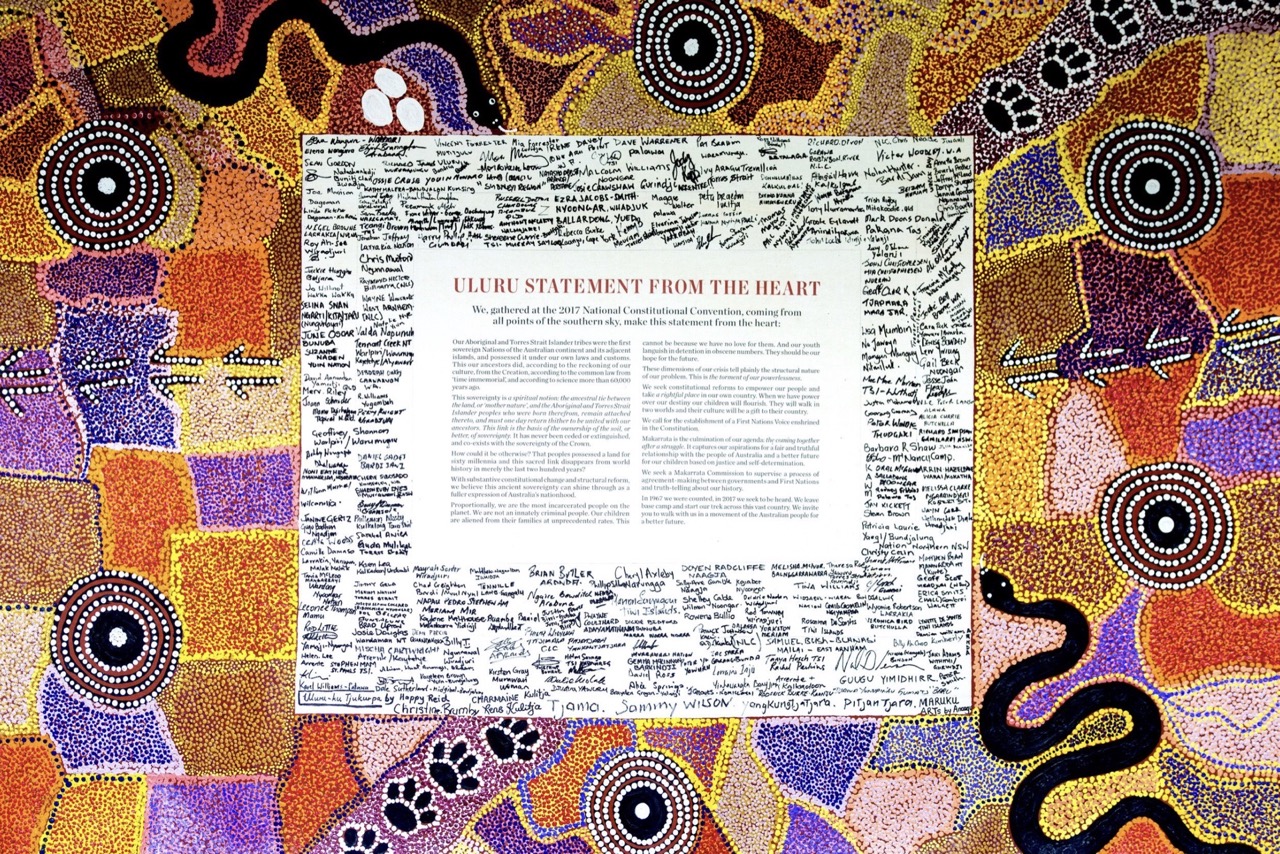

Most recently, in 2017, over 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders representing their people ‘from all points of the Southern Sky’ gathered in Central Australia. This followed a series of regional dialogues across the country, held by and for Indigenous Australians. The outcome of the 2017 gathering was ‘The Uluru Statement from the Heart’.

Despite all that has gone before, the Statement invites all Australian people to create a better future together. It proposed just two reforms: practical recognition of First Nations’ sovereignty through a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Australian Constitution, followed by ‘Makarrata’, a formal process of agreement-making and truth-telling.

The Statement, and the call for a Voice, is not knee-jerk, defensive or self-centred. It doesn’t attribute blame. Instead, it offers possibility. These leaders are standing up and saying ‘Be with us on this’. They write: ‘…we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood’. It’s not ‘either…or’. It’s ‘both…and’.

In just 429 words, the ‘Uluru Statement from the Heart’ is an example of emotionally healthy community leadership on a grand and ambitious scale. Its call for a Voice is not an attribution of blame nor a call for revolution. It’s a simple request for a greater say in their own destiny so that their children can ‘walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country’.

Gayle