There’s an important principle we use in emotional health that we haven’t covered in this blog for some time. The principle of self-centredness – along with topics we have discussed including the line of choice, the inner observer, the centres of intelligence and behavioural freedom – is an important concept to understand as you continue your journey towards raising your level of emotional health.

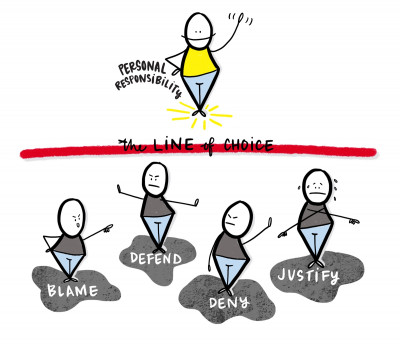

Regular readers will remember the distinction between above- and below-the-line responses in terms of taking personal responsibility (above the line) as opposed to resorting to blame, defensiveness, denial and/or justifying (below the line).

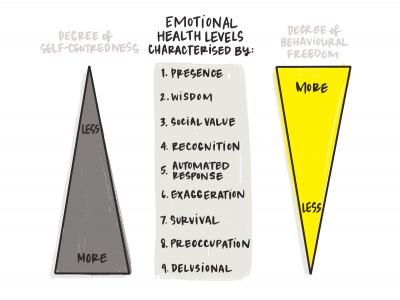

Another way of looking at this distinction is in terms of ‘self-centredness’ or, more specifically, the ‘degree of self-centredness’ that a person has. This is the degree to which we are specifically focused on ourselves to ensure that we will survive in our environment. As such, it also represents the degree to which we engage our defence mechanisms in an attempt to make sure we will feel safe.

A person with a high degree of self-centredness will tend towards blame, defensiveness, denial and justification in response to challenging situations.

In contrast, a person with a low degree of self-centredness will be quick to consider the point of view and wellbeing of others as they go about their life. They tend to embrace the notion of the ‘greater good’. They take personal responsibility for the impact they have on others, seeing themselves as one part of the wider community.

In our work we see self-centredness as a continuum. You are not self-centred or otherwise. Rather, each of us has a degree of self-centredness and the more emotionally healthy we are, the less self-centred we become.

Further, our degree of self-centredness is closely associated with our degree of behavioural freedom. As our degree of self-centredness decreases, our degree of behavioural freedom increases.

A person with a low level of emotional health will display self-centred, below-the-line reactions to situations they encounter, and they are less likely to be capable of responding in any other way (they have a low degree of behavioural freedom). As they work to be less self-centred, they will more often display above-the-line responses to similar situations, taking personal responsibility and being more aware of the impact of these situations, and their own behaviour, on those around them.

As with most other aspects of emotional health, we can develop the capacity to act with a lower degree of self-centredness, beginning by drawing on our inner observer to better understand our automatic reactions and ultimately choose more emotionally healthy responses more often.

Gayle

———

Image credit: Hulki Okan Tabak on Unsplash